Preface: The Funk in 2020

December 2, 2020

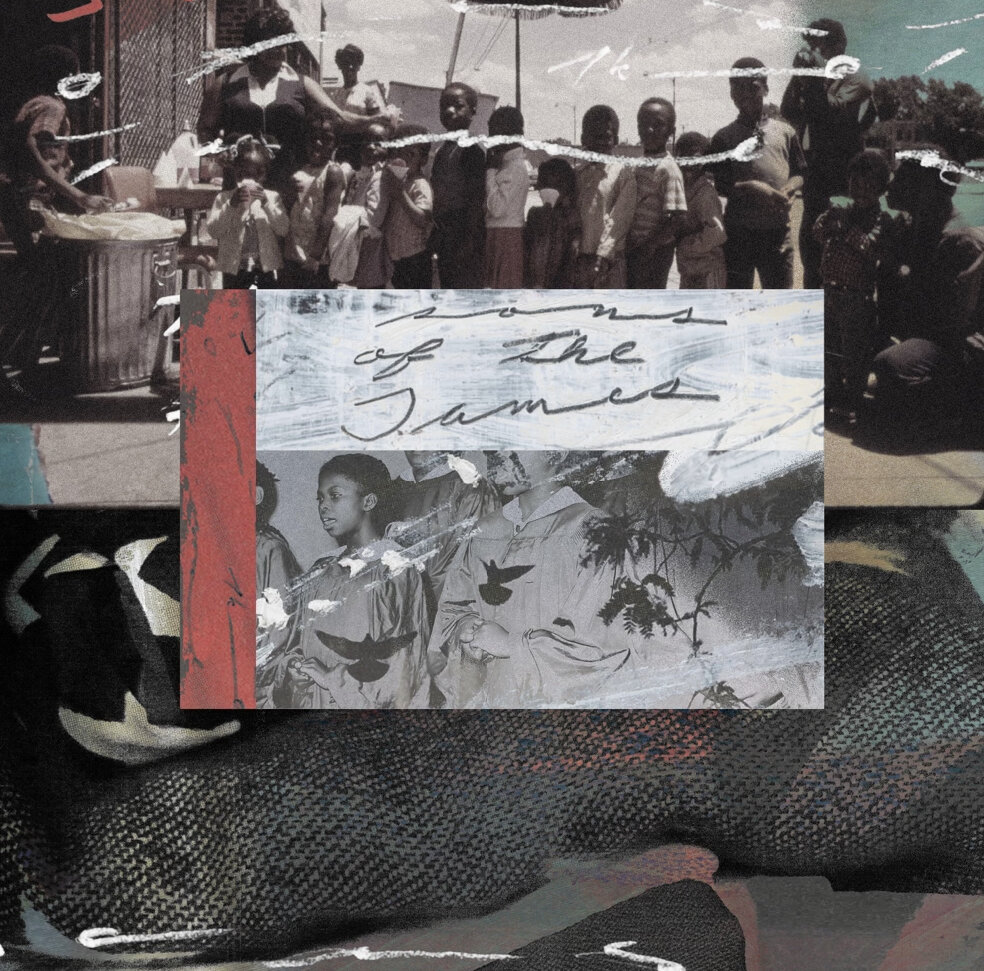

Illustration by Malaaya Adams

Funk belonged to poor black city folk whose space in the world always seemed to be in a kind of apposition or opposition with cultures of hegemony, imperialism, capitalism and systems of assimilation into a white world. These were nappy niggas, you know, who ain’t want to “be” nobody’s idea, and this often meant “bringin’ the funk.”

– azami aman, Liner’s Notes for Blues Folk

Funk, as poignantly explained by James Brown to a young Bootsy Collins, is about the 1. He would say to Bootsy, “Son, you gotta give me that 1, you play all that other stuff, just give me the 1.” What Mr. Brown was explaining to Bootsy was a core principle of the music, especially from the bassist. The bass, along with the kick drum, carries the sonic frequencies on the low end of the spectrum - it’s the booty of the music, and in funk, the downbeat is primarily accentuated by the bass.

Like most forms of Western music, funk places primacy on the first beat of a measure, but in this music, this emphasis is sacred. In funk, the 1 is both an anchor and a guide: no matter if you’re lost or astray, in bondage or held captive, if you find the 1, you can find home. Equally important, funk is about space. You emphasize the 1, but you leave beats 2, 3, and 4 open to possibility.

Bootsy Collins demonstration.

After a labor dispute with Mr. Brown, Bootsy took these lessons to Detroit where he would eventually meet George Clinton. With Clinton, they married the 1 with the funk and put it on acid, creating new worlds and sonic landscapes. The music was James Brown, but with screaming guitars; Hendrix, but with a bottom so low it could grab the depths of anyone’s soul, if you let it.

Funk emerged as a form artistic expression by Black musicians during the late 1960s and early 1970s, coalescing with the Black Power Movement and movements for Black liberation. James Brown, Sly Stone, George Clinton and Bootsy Collins, and countless others embedded messages of liberation, critiques of empire, revolution, and love in the music. Listening to any number of musicians, artists, or listeners talk about funk, you quickly realize that funk is more than a genre - it’s a way of life, a spiritual experience, a continuation of spirituals and the Blues, a way of living otherwise.

In 2020, a year filled by tragedy and plunder at every turn, several artists have continued in this tradition of Black music – asking questions about the world we live in and envisioning a new one. To name a few: Butcher Brown, a band from Richmond, Virginia; Adeline, a French-Caribbean bassist and singer-songwriter; Cory Henry, an organist and singer-songwriter; Kirby, a singer-songwriter hailing from Mississippi; Sons of the James, a duo featuring singer-songwriter, Rob Milton and producer/multi-instrumentalist, DJ Harrison; MonoNeon, a bassist from Memphis, Tennessee; Thundercat, a bassist and singer-songwriter from Los Angeles, California. These artists, along with countless others, have all shown us what funk can be and sound like in 2020. In their own way, each of these artists has continued in the tradition set forth by others, cutting against the sonic landscape of the present to interpret a familiar sound in a new way.

In the next few days, we’ll be exploring the funk in 2020, in all of its glory and ugliness. Particularly, we’ll be looking at the music of Cory Henry and the Funk Apostles and Adeline, asking the question of what does the funk has to say in this time?

The Plug’n Play: The Funk in 2020

You can listen to the full playlist on Apple Music, Spotify, or Tidal